By Biran Gaye

On a December night in 2004, bullets tore through the darkness on Sankung Sillah Factory Road, ending the life of one of Africa’s most unflinching journalists.

Deyda Hydara—co-founder of The Point newspaper, and correspondent for AFP and Reporters Without Borders—was gunned down just days after he’d vowed to fight repressive media laws threatening to strangle Gambian journalism.

Twenty years on, justice stirs haltingly in The Gambia with the recent arrest of Sanna Manjang, one of those accused of carrying out Hydara’s assassination.

In the two decades since, Hydara’s contribution to press freedom and accountability has come to symbolise both the high price of speaking truth to power and the resilience his death sparked among Gambian journalists.

A Life Built on Principle

Hydara was more than a byline or a masthead; he became the conscience of Gambian journalism.

His “Good Morning Mr President” column didn’t just dissect policy or question those at the top—he made accountability personal, week after week, even as President Yahya Jammeh’s regime grew more oppressive.

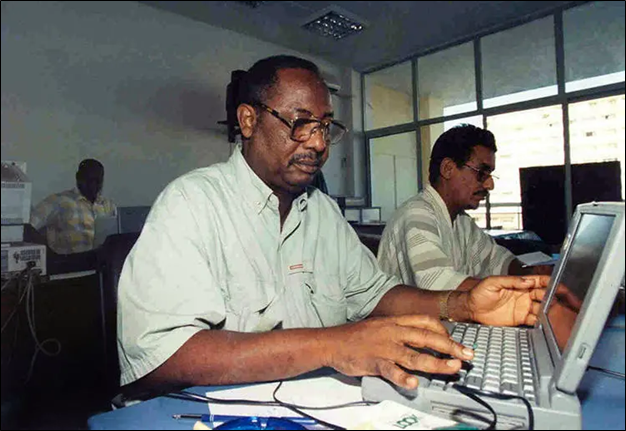

“He was a generous guy, very good PR with people, and he was always fostering relations,” recalls Pap Saine, Hydara’s friend and business partner. But it was Hydara’s professional courage that truly defined him.

By co-founding The Point and helping establish the Gambia Press Union, Hydara gave his colleagues tools to defend their profession.

His work with international organisations like the AFP and Reporters Without Borders connected The Gambia to global networks of advocacy, ensuring the world saw every attack on Gambian journalists for what it was: a threat not just to individual reporters but to the very prospects of democracy.

Defiance and Sacrifice

In December 2004, The Gambia’s National Assembly (Parliament) passed two contentious pieces of legislation that represented a frontal assault on media freedom.

Law makers repealed the National Communication Act of 2002, but amended the Newspaper Registration Act with provisions that would effectively place a financial barrier to independent newspapers and turned alleged speech crimes into jailable offences.

For example, the registration bond for newspapers was increased tenfold—from 50,000 Dalasi to 500,000 Dalasi—putting independent media financially out of reach for most journalists.

Simultaneously, amendments to the criminal code dramatically increased penalties for defamation and sedition, imposing lengthy jail terms that could destroy journalists’ lives and careers.

These laws were designed to intimidate, to silence, to control. But Hydara, true to form, denounced the laws publicly, promising to challenge them.

Two days after that act of defiance, on December 16, 2004, Hydara was ambushed while driving home from the office around midnight, accompanied by two Point Newspaper staff members, Ida Jagne-Joof and Nyang Jobe.

As they travelled along Sankung Sillah Factory Road toward New Jeshwang, a Mercedes-Benz taxi suddenly overtook their vehicle.

Without warning, gunmen in the taxi sprayed his car with bullets. One struck him in the head, another in the chest. He died instantly, while his two colleagues sustained serious injuries.

Survivors would later identify their attackers: members of Jammeh’s infamous “Junglers”—state hitmen whose mission had been unmistakably clear.

The Fallout

Hydara’s assassination sent shockwaves through Gambian society and dealt what Pap Saine describes as “an irreparable cost” to the nation’s media landscape.

“I felt down,” Saine recalls of the night he learned of his colleague’s death. He had just presided over a wedding ceremony for his brother—a ceremony Hydara was supposed to lead.

At the hospital, Saine waited for hours as Hydara’s body was brought in. “I was crying,” he remembers. A nurse, recognising the danger, warned him that he too could be targeted and advised him to hide in the guard room.

The message was unmistakable: speaking truth to power in Jammeh’s Gambia could be fatal.

The killing was not merely the loss of one journalist; it was an attack on the very possibility of independent journalism in The Gambia.

The murder threw Gambian journalists into terror. Many fled; others self-censored or gave up.

Saine, urged by family to abandon journalism, refused. Instead, he made The Point a daily newspaper, clinging to Hydara’s vision even as he himself landed in jail—multiple times.

Countless colleagues across the country faced torture, prison, and harassment.

Yet The Point survived. It became both legacy and living testament, enduring even as other papers vanished and repression thickened.

“This newspaper suffered a lot. Not only my dad. Uncle Pap went to prison. And then others and others and others,” notes Baba Hydara, Deyda’s son.

“It’s an institution that should be really put up there with institutions that did a lot for this country.”

Justice Delayed, Not Denied

International recognition followed Hydara’s death—awards from New York to Vienna—, but for his family and country, that meant little without justice.

That hope flickered with the launch of The Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission.

The commission laid bare the state’s campaign against the media and identified those who ordered and carried out Hydara’s assassination.

More recently, justice appears within reach: Sanna Manjang, one of the gunmen, sits before a Gambian court.

“It shows us that we can do it,” says Baba Hydara, who returned to The Gambia from the United Kingdom, not just to sustain The Point newspaper but to see his father’s killers face trial.

“We’re trialling him in our own high court. We didn’t need no [sic] hybrid court or anything else.”

A Legacy That Refuses to Quit

Walk into The Point’s newsroom, and you still find Hydara’s portrait and his “Good Morning Mr President” column on page one every Monday, now penned by Saine.

The paper still insists on old-fashioned verification and reporting—no easy feat in an age of social media shortcuts and dwindling advertising revenue.

For the new generation of Gambian reporters, Hydara’s example remains more valuable than any press law.

Since Jammeh’s removal from power, the climate for journalists has warmed. “We have very good improvement…we don’t have problems like before.

“Before, journalists were killed, houses burned, and offices burned. But now, thank God,” Saine says.

Yet challenges linger: the print industry bleeds revenue, online misinformation moves faster than fact, and full justice for all Jammeh-era abuses remains unfinished business.

“Denying justice is not easy,” Baba Hydara stresses. “Most victims are dying, some lose interest in even going to court. Evidence fades.”

The family still hopes for a memorial at the spot where Deyda was killed—something to remind the next generation what it costs to speak freely.

Courage Echoes

For the Hydara family, December 16th holds a double meaning. It was the day Deyda intentionally launched The Point on his wife’s birthday—and the day he was killed. Every anniversary since his death carries an uneasy blend of pride and grief.

“It’s very difficult. It’s a reminder every year,” says Baba Hydara. “But from that brutality, inspiration grew.

“Investigative journalists across the country still draw courage from his example—refusing to flinch, demanding answers.

“Since his tenure, he’s been very tolerant when it comes to the media,” Baba Hydara observes of President Adama Barrow’s administration.

“So I applaud that—that he’s letting things happen as they should be. That is a major free country without oppression whatsoever from government.”

It’s not perfect—but the freedom to write, report, and criticise now has roots even Jammeh couldn’t rip out completely.

Hydara’s killers tried to silence him, but they only amplified the call for truth. As one tribute put it: “Although Deyda Hydara has died, his voice was [sic] not.”

The stretch of Sankung Sillah Factory Road where he fell is quieter these days. And yet, Hydara’s legacy still echoes—proof that even in the shadow of violence and fear, the fight for honest journalism can and will outlast the guns.

His pen was mightier than their weapons. That’s the honest reckoning—and the ultimate cost and gift of his sacrifice.