When tragedy strikes a small community, the shockwaves travel fast and deep. The Senegambia Observer recently visited the quiet village of Sare Bohum to witness firsthand the sense of mourning—and anger—that’s settled over the village. The source of their grief is painfully clear: the recent death of an infant following a case of female genital mutilation (FGM), and the court’s decision that followed.

A Village in Mourning

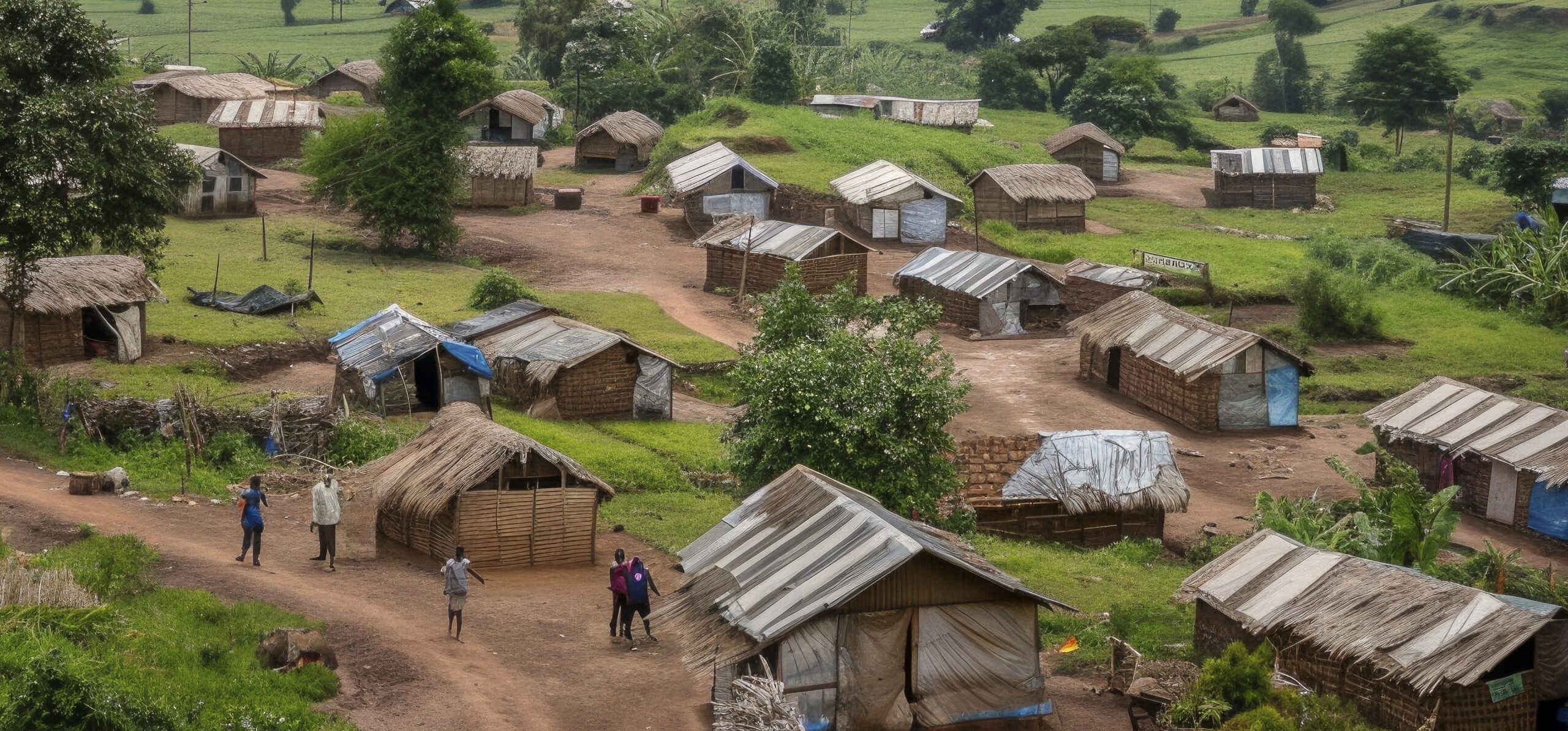

In the quiet village of Sare Bohum, where the morning sun casts long shadows across dusty paths and cattle graze lazily under the sparse shade of neem and baobab trees, a sorrow deeper than the wet humid soil beneath the green grasses, has struck the hearts of its people. With fewer than a thousand residents, this small Gambian village hugs the border with Senegal.

Here, time is measured by the seasons—subsistence farmers work the soil with their hands in the rains, men gather in clusters under makeshift canopies in the dry heat, and women tend to their homes as smoke rises from thatched roofs and barefoot children run between compounds. Life is simple, cyclical, and for the most part, peaceful—until tragedy shattered the calm in September 2025.

The Fatal Journey

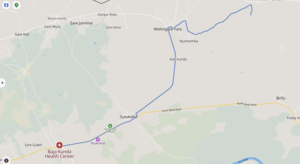

The stillness was broken when a newborn baby girl, just three weeks old, was rushed along Sare Bohum’s bumpy, winding tracks toward the distant Baja Kunda Health Center. (18 KM from Sare Bohum).

Her mother, Adama Sowe, and grandmother, Sillah Gagigo, accompanied her, desperate and afraid. The infant’s tiny body was weakened by severe vaginal bleeding. Despite urgent efforts by doctors—first in Baja Kunda, then in Basse District Hospital, and finally at Bansang General Hospital—nothing could be done. The baby girl bled to death, her life lost before it had truly begun.

Hospital authorities confirmed the cause: female genital mutilation (FGM), a practice banned in The Gambia for a decade but still carried out in secrecy in many rural villages. Police were summoned. Both the mother and grandmother confessed to the circumcision, and the case was transferred to Basse Police Station.

The news sent shockwaves through Sare Bohum, a place where life revolves around livestock and millet, where men debate the price of cattle in the shade and women raise generations in the glow of cookfires. The death of one child brought grief, anger, and a painful reckoning.

The Arrests and Aftermath

Within days, four people from the village were arrested—three women and one man—including the woman who performed the circumcision. At Basse Magistrate Court, before Magistrate Peter Ado Che, the charges were read in Fula.

Sillah Gagigo, the step-grandmother; Metta Wamch, the alleged cutter; and Adama Sowe, the mother of the deceased, pleaded guilty. The two women were fined D10,000 Dalasi ($140) each, while Metta Wamch’s case, which could carry a life sentence, was referred to the High Court.

Mansour Sowe, the baby’s father, pleaded not guilty and was granted bail, with his case now progressing in court.

Gambian lawyer and rights advocate Musu Bakoto Sawo questioned the legality of sentences handed down in the case, saying they contradict the Women’s (Amendment) Act, 2015.

“Under what law were these sentences imposed? A child died, yet the perpetrators are walking away with mere fines. How is this going to deter anyone?” she asked, warning that leniency only encourages continued practice of FGM.

Voices of Pain and Protests

Sare Bohum’s sorrow has become a national and international flashpoint. The case has drawn condemnation from human rights groups and anti-FGM campaigners, who point to the devastating effects of FGM—severe bleeding, infection, infertility, and death among them. Survivors endure lifelong physical and psychological scars.

“Since I got married, I’ve never known pleasure in sex—just pain,” Aminata Manjang (not her real name), confides. “I only do it to satisfy my husband. I don’t want my daughters to go through what I did.”

She describes a harrowing childbirth, made worst by FGM: “Every time I have a baby, they have to cut me again just so the baby can come out. Then they stitch me back. I only learned it was because of FGM after my third child, when the midwife told me, ‘Since you people don’t stop FGM, you’ll continue to suffer like this.’”

Aminata vows to spare her own daughters the blade. But she knows not every mother can – or dares to – defy tradition.

Since I got married, I’ve never known pleasure in sex—just pain. I only do it to satisfy my husband. I don’t want my daughters to go through what I did.

Aminata Manjag, FGM Victim.

In Sare Bohum, as in many Gambian villages, the practice persists—sustained by cultural norms, pressure from elders, and the weight of tradition. Some women, speaking under anonymity, insisted FGM could be preserved safely. “It is something we have always done,” one explained. “But now, it can be controlled medically.

If proper care is taken, it does not have to be fatal.” Her companion nodded, emphasising that with modern precautions, the ritual could continue without endangering children.

Contrasting these voices, Biram Sowe (not his real name – doesn’t want his real name published), a father of four from the village argued for abolition. “This is a harmful practice,” he said. “It brings nothing but pain, shame, and death. It has no place in our future, and we must stop it before more children are lost.”

The debate in Sare Bohum mirrors divisions across The Gambia—between old and young, rural and urban, those clinging to custom and those urging reform.

Despite a national ban on FGM since 2015, the law’s reach is limited in remote places like Sare Bohum, more than 20 kilometers from the nearest town and accessible only by rutted tracks that turn to mud in the rainy season.

Enforcement is sporadic, prosecutions are rare, and communities often close ranks to protect their own. Earlier this year, the National Assembly narrowly upheld the FGM ban after fierce debate, a decision hailed by activists but resented by some traditionalists who see the law as an assault on their way of life.

The death of the baby has forced the village to examine its conscience. In homes and under shade trees, the tragedy is discussed in hushed tones. Some elders, shaken by the loss, have begun to question the wisdom of inherited practices.

Others, fearful of police intervention, have doubled down on secrecy. The local midwives and cutters—once respected—now face suspicion and, in some cases, ostracism. The air in Sare Bohum is heavy with uncertainty, grief, and a tenuous hope for change.

The Limits of Law

The implications ripple outward. Nationally, the case has galvanised anti-FGM campaigners and prompted renewed calls for education, community engagement, and support for survivors.

Sophie Manneh is the coordinator of Safe Space for Girls—an initiative that empowers women to freely discuss sensitive women’s health and well-being. She was outraged when three women convicted of FGM in the Upper River Region were fined D10,000 ($140) each. “You can’t exchange a child’s life for money—certainly not for D10,000,” she says. “That verdict sends the wrong message: that FGM isn’t serious.”

Barrister Ngenarr Yassin Jeng, a gender rights advocate, agrees. “D10,000 is not an appropriate fine, given that the infant ended up dying.

“The prescribed fine under the Women’s Amendment Act is D50,000 for active participants and D10,000 for non-disclosure.” With family members involved, “the highest fine and conviction should be administered,” she said.

In Sare Bohum, and across The Gambia, ending FGM demands a fundamental shift in attitudes—one that can only be achieved through dialogue, empathy, and the slow work of changing hearts as well as minds.

But there is resistance. Some in Sare Bohum, and in similar villages across the country, resent outside intervention and fear the erosion of their identity. The challenge for anti-FGM campaigners is to work within the fabric of rural society, to respect local realities while insisting on the rights and dignity of girls. “Ending FGM will take more than laws,” one activist said. “It requires courage, compassion, and a willingness to listen—even to those who disagree.”

Can Sare Bohum Lead the Way for a Future Without FGM?

As the sun sets behind baobab silhouettes and dust rises from cattle tracks, Sare Bohum is left to mourn, to reflect, and, perhaps, to change. The voices of women—some scarred by FGM, some determined to protect their daughters—echo through the village. The tragedy of one baby girl has left an indelible mark, a reminder that the future depends on the choices made now.

The journey ahead is uncertain. Whether Sare Bohum becomes a symbol of transformation or returns to old ways will depend on the courage of its people, the resolve of its leaders, and the support of a nation wrestling with its conscience.

What is clear is that the death of one child has changed the conversation. Sare Bohum stands not only as a site of grief, but as a crossroads—a place where The Gambia’s struggle between tradition and progress is being played out in real time.

A future without FGM promises safety and dignity for girls in Sare Bohum and beyond. It offers hope that generations to come will not have to endure the pain of a harmful tradition, and that villages across The Gambia will one day greet the morning sun with laughter, not sorrow.